St. Julien

The World War One Battlefields site is undergoing a major update, with pages being converted to a new, user-friendly mobile format. The updated pages can be found at Updated World War One Battlefields. Some pages such as this one remain in the original format pending update.

The road from St. Julien to Ypres during the War. Photo: NELS

This village, today known as St. Juliaan, can be found a little to the north-east of Ypres, on the N313. Here and at nearby Langemarck was where, in the words of Hutchinson, "the tiny army of seven Divisions of 1914 stood it's ground before the pick of the world's greatest military force". The village was however taken by the Germans during their attack using gas for the first time on the 24th of April 1915, and then they held it for two years. It was only recaptured during Third Ypres, when it was taken on the first day (31st of July 1917) by the 13th Royal Sussex.

Seaforth Cemetery, Cheddar Villa

On the main N313 road a little south-west of the village is Seaforth Cemetery, Cheddar Villa. Cheddar Villa was the name given to a farm on the west side of the road, and on the 25th and 26th of April 1915, during the battle of St. Julien there was severe fighting here. The British dead were buried here at this site, and the Cemetery originally named Cheddar Villa Cemetery. The name was changed in 1922, at the request of the Commanding Officer of the 2nd Seaforth Highlanders, as so many men from that battlaion were buried here. Nearly 150 soldiers were buried here, 21 "Known Unto God" and 19 whose graves were later destroyed by shellfire (now commemorated by special memorials).

Exact details of many of the burials were probably not recorded, as graves A8 and B1 are actually long rows of burials, and the headstones for the soldiers buried in them are not above thegraves, but instead set against the cemetery walls, so there appears to be a large open space in the centre of the cemetery, as shown in the picture above. Two large stone markers, known as Duhallow Blocks (shown below), commemorate the 75 and 18 soldiers respectively that were buried in these mass graves. These can be seen in the foreground of the photo below.

Mass grave markers at Seaforth Cemetery

A panel set into the far wall also lists the names of another 23 Officers and men of the 2/Seaforths who fell near here, but are not known to be buried in the cemetery. Their names are "officially" recorded on the Menin Gate, along with other soldiers who have no known grave.

Panel listing missing Seaforth Highlanders

Some graves always catch your eye in any cemetery, and here the inscription on the memorial stone for Corporal Benjamin Anderson is "He was ours & we'll remember. From widow and children". A short but heartfelt inscription, and the CWGC website records that his widow was Jeanie Anderson of Caledonian Crescent, Edinburgh. The inscription on Private George Tait's grave reads "Home is not home since you are not there. By his mother." It is impossible to read these inscriptions and not think about the grief that lay behind them, and the hours spent in searching for the way to honour the loss of a husband or a son in a dozen words or less.

On the memorial stone for Private A J H Arnott there was no inscription, and not even his Christian names or his age are recorded by CWGC. However, he was still remembered; at the base of the stone was a small photograph of this man. Such photographs are becoming a more common sight in the war cemeteries, and it is always moving to look at the face of one of those who fell ninety years ago.

Memorial stone for Private Arnott, and his photograph beside it

Against the right hand wall is a row of headtones commemorating Northumberland Fusiliers. There are 18 in total, although four are not identified, just commemorated as men of that battalion. However, this is a row of special memorials (Row 'D'), commemorating these men buried together in grave A8. These men, mainly Territorials serving in the battalions which made up the 149th Northumberland Brigade, died on the 26th of April 1915. This was the Battle of St. Julien, a British counter-attack following on from the German Gas attack a few days earlier.

The position of the lines at that time meant that the Northumberland men attacked more or less northwards, probably just north of where the cemetery now stands. The attack was meant to commence, in accord with other units, at 1.20 p.m., but the order for the attack was not even receieved until 1.30 p.m. Three battalions (the 1/4th, 1/6th and 1/7th Northumberland Fusiliers) attacked twenty minutes later. They had little information and did not know the ground well. The attack of the Lahore Division, to their left, had faltered, and the Northumbrians suffered from enemy shells as well as machine-guns firing from Kitcheners Wood (see below). The 149th Brigade advanced as far as they could and took up a position in some old trenches. The Brigade lost nearly 2,000 men that day, including their Commanding Officer Brigadier General James Riddell - just one of the senior officers who fell in the Great War. He is buried at Tyne Cot.

There are excellent views from this cemetery in all directions across the flat Flanders landscape.

Nearby is the farm which was known to the troops as Cheddar Villa. A farm now stands just to the right of the Seaforth Cemetery, and there is a large bunker visble from the road. This bunker was a German strongpoint, which was taken on the opening day of Third Ypres. It was then used by British troops, but its large entrance (having been built by the Germans) now faced the enemy, making it a dangerous place. On the 7th of August 1917 a first aid post was set up within the bunker by the 3/Ox & Bucks Light Infantry when they took over this part of the line. A platoon was also sheltering here when a shell came straight into the entrance opening - with awful but predictable results. Many there were killed, and many "horribly mutilated" according to Brice. Silent pickets can be seen in the fence by the field here.

A farm located just west of Seaforth Cemetery was known initially as Shelltrap Farm to the troops. The Holts report that this was changed by Corps order to Mousetrap Farm (presumably a name with less worrying connatations, although names such as Hellfire Corner, Shrapnel Corner and many others remained!). Whatever the reason, trenchmaps of April and June 1917 do mark the site as Mouse Trap Farm. Extracts from these and many other trench maps can be found on the excellent Paths of Glory website. The soldiers probably still referred to it as Shell Trap Farm, as a pamplet published by the Ypres League in the 1920s used that name when describing the position of the narby demarcation stone.

Will Bird, who served with the Canadian Forces during the First World War, described visiting this area in the early 1930s.He described how, in a single field to the north of the road were twenty-two pillboxes. There was also, then, a maasive German gun emplacement right next to the Seaforth Cemetery.

Kitcheners Wood

From near the Seaforth Cemetery and bunker, a small road leads off to the left towards where this wood used to stand. The wood no longer exisats, but a memorial is set by the corner of a house, next to a large warehouse structure which can be seen from main road and stands out as the words Beton Bquw are painted in white on its roof.

Kitcheners Wood Memorial....in the garden of a house

The perspex panel fixed to the front of the memorial shows a map of where Kitcheners Wood used to stand, and has the statement "During the night of April 22nd 1915 after the first chemical attack in warfare, the 10th battalion (Alberta Regiment) and the 16th battalion (Canadian Scottish) retook Kitcheners Wood".

These battalions were involved in holding the line in the face of the German gas attack in April 1915.

The 16th Battalion had trained in England, and upon arriving there in December 1914 had experienced a trying time initially. On December the 1st, a night training exercise on Salisbury Plain had to be abandoned due to torrential rain, and several times in early December their War Diary makes plaintive reference to their camp (at Westdown) being "frightfully muddy". They sailed for France on the 13th of February 1915, but their ship struck severe gales and several horses were killed during the journey.

On the 21st of April 1915, having just come out of the front line, they were billeted in Ypres. The next day, the 22nd, in the afternoon, the Germans started shelling the town heavily. Something was obviously afoot, and the 16th Battalion war diary records that there was panic among the inhabitants of Ypres, with civilian refugees pouring into the town, and many French soldiers (mainly French colonials - Zouaves) in flight.

At 7.40 p.m. the battalion was ordered to the 3rd Brigade HQ. This was actually based at Shelltrap (or Mousetrap) Farm, although at that point in the War the farm was known as Farm C.22.b. On arrival at the Farm they were tasked to support the 10th Battalion which had already arrived, in an attack, originally scheduled for 10.30 p.m. on the wood "north-west of St. Julien" - Kitcheners Wood. The name incidentally has nothing to do with Lord Kitchener, but derived from a translation of the original name of the wood.

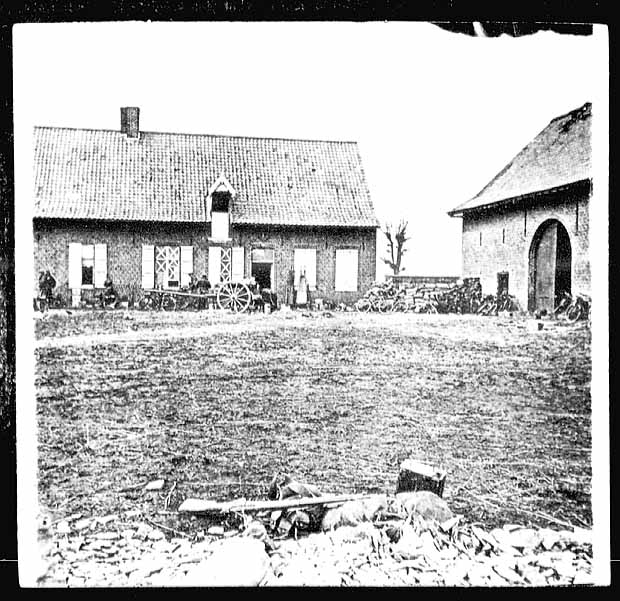

Farm C.22.b - later Shelltrap Farm, or Mousetrap Farm. Photo from the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade War Diary, Collections Canada

The two battalions formed up just to the north-west of where Seaforth Cemetery is located today.

The 10th were in position first, and the attack was delayed whilst the men of the 16th formed up in the moonlight. The 10th battalion was in front, with two companies each in two lines; A and C at the front with B and D behind. The 16th supported them, around 30 yards to their rear. The woods loomed up in the moonlight to their front about 700 yards away. They could also see a house, which was predicted to contain German machine-guns, and did.

The order to attack was given at 11.48 p.m., and the 2nd battalion's war diary describes it almost lyrically : ""not a sound was audible down the long wavering lines but the soft pad of feet and the knock of bayonet scabbards against thighs." Imagine advancing in the moonlight as silently as possible, towards an armed enemy line....their hearts must have been in their mouths.

Until the Canadians got to within 300 yards, there was no reaction from the German defenders (men of the 2nd Prussian Guards and the 234th Bavarian Infantry Regiment). Then the Canadians encountered a hedge, and the noise they made getting through this obstacle alerted the Germans who opened fire with rifles and machine-guns, and also sent flares up. The attackers lay down at first, and then those who were not hit rushed forwards and reached the German trench, attacking with bayonets and the butts of their rifles and clearing the trench in less than a minute. The 10th battalion diary reports that many Germans then encountered wanted to surrender, but as some kept firing very few prisoners were taken and many were killed. The 16th battalion war diary records 100 Germans were killed, 250 wounded and 30 taken prisoner in this action.

The Canadians then pressed on into the wood, where the men of the 10th and 16th battalions became somewhat mixed up. They came across four large guns, believed to be ones abandoned by the French but described in later accounts as British guns abandoned by the 2nd London Battery Royal Garrison Artillery.

The Canadians advanced through the wood, reckoning their direction by the North Star. More Germans were encountered and "disposed of", and a note in the 16th Battalion war diary records that men were "cautioned against dealing harshly with prisoners".

They advanced a few hundred yards and reached the far side of the wood, and tried to establish a line there. However, the Germans were on their flanks, and they could not obtain enough reinforcements quickly, and so they fell back to a line of German trenches just to the south of the wood, and then back to the hedge which they had forced their way through earlier on.

Those surviving then dug a trench about 2 feet deep, with a parapet. A parados (a bank behind the trench) was also needed, due to the Germans flanking them. This trench was filled with dead and wounded, including some Germans. One of the wounded Germans, a Colonel, was sent back to the rear, presumably for interrogation. The Canadian soldiers in this trench were being fired on from all directions except the south-east. The trench was about 200 yards long, and the 10th were on the left flank with the 16th mainly on the right.

At 6.30 a.m. on the 23rd, there were just five officers and 188 other ranks of the 10th Battalion in this position - 816 men in total had started the action. There were only five officers and 263 other ranks of the 16th Battalion remaining.

As there were still more men than the trench could safely hold, they ran communication trenches back to their rear towards an area where the ground was "dead" to the enemy. From dawn on the 23rd, all day and in the evening they were shelled, taking casualties, but held on. They were initially ordered to make a further advance at 7.30 p.m., but those orders were later cancelled.

The field guns in the woods are described after the action as being "piled high with dead". It was impossible to recover these on the night of the 22nd/23rd, as no horses could have been brought up, and if men had tried to haul them back they would have been open to hostile fire. They were instead destroyed by engineers to prevent the enemy making use of them.

As night fell on the 23rd, requests for more ammunition and for stretchers were sent back. Lt Critchley of the 10th made some journeys under darkness back to the 3rd Bde HQ, seeking machine-guns and flares. At nearly midnight on the 23rd, some rations were brought up. The night of the 23rd/24th seemed quiet at first, but at 3.30 a.m. coloured signal rockets were fired by the Germans, and shortly after shells started falling to their right. At 4 a.m. they thought they could see a gas cloud approaching. The Germans were starting a series of counter-attacks along the front.

In the early morning, the 10th were ordered to come out of their lines to support another unit (the 8th Canadian Battalion) on Gravenstafel Ridge. It was light by now, and withdrawal was in view of the enemy. By 4.45 a.m. most of the 10th were out, with the 16th spread out holding the trench. However, about 20 men and two of their officers could not get out due to the large number of dead blocking the trench. They finally made it about 15 minutes later, but by then the remainder of the 10th had moved off. The 16th Battalion were then relieved by the 2nd Canadian Battalion. This must have been a highly risky operation. It was performed in daylight, close to the enemy and the relief was literally conducted with one man at a time leaving and being replaced by one from the 2nd Battalion. Incidentally, the 10th Battalion reported to the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade HQ and were sent off on their next task - despite the fact there were now just 3 officers and about 150 men remaining. They were under fire again in their new location within an hour or so.

The cost of this vital operation was high. There were dead and wounded lying all around, and the dressing station struggled to cope. Later that same day, the 2nd Battalion were ordered to retire from the trenches which the 16th had gallantly held.

A subsequent note made by Major D.M. Ormond in the 10th Battalion War Diary says that "there were many wonderful and brave deeds done by men of the 10th Bn, but all were doing such deeds that one could not be chosen as outstanding above others".

Many of course paid the ultimate price, and because of the nature of the action, many sadly have no known grave. The War Diaries list only officer casualties by name, and Captains H Wallace, J Nasmyth and Lieutenants Ronald Hoskins and D McColl are commemorated on the Menin Gate. Ronald Hoskins family was from near Exeter in England. Lieutenant-Colonel Russell Boyle was wounded, and later died of his wounds on the 25th of April and is now buried at Poperinghe Old Military Cemetery. He had signed as Approving Officer for the 10th Battalion the Attestations of some of those who had also died, including Ronald Hoskins and Lieutenant Albert Ball. Albert Ball was also wounded in the action at Kitcheners Wood, and survived long enough to begin the journey back to Canada. However, he died on the 29th or 30th of April, and is buried in Quebec.

St Julien Dressing Station Cemetery

St Julien Dressing Station Cemetery is located off a small road leading off to the right from the main road, within the village itself. This area and the cemetery itself was damaged by shellfire in the summer of 1918. The cemetery was started during the war in September 1917, and is irregular both in shape and in the layout of the graves.

St Julian Dressing Station Cemetery

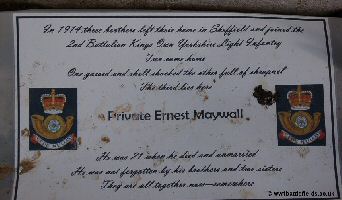

After the Armistice, more graves were concentrated here, and there are now 420 buried or commemorated here. One of the graves here is that of Ernest Maywall, of the 2nd Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. At the base of his grave was information about the family; four small woooden crosses at the corners of a sheet showing their names - Mabel, Harry, Lillian and George.

Three Maywall brothers from Sheffield served; the other two returned home

The children were born to Isaac and Elizabeth Maywall, who in 1901 were living in Attercliffe, Sheffield, where Isaac was employed as a steel moulder.

Many of the 180 unknowns buried here have headstones which show at least their unit or their rank. In the far left corner is the solitary grave (3C) of Second Lieutenant Robert Dyott Willmot, of the 2nd Kings Royal Rifle Corps who died, aged just 19, on the 17th of February 1918. The inscription on his headstone reads "In paths our bravest ones have trod, O make us strong to go." He was the son of George and Nellie Willmot of Warwickshire. The inscription on the headstone of Corporal Arthur Malins of the 12th Londons reads "Gone but not forgotten by his loving wife and child".

Other Sites

From the village, down a small road to the left are the remains of a large German bunker which was known as Alberta. It used to be posible to venture nearer to it, but now one can only see it from a distance. A large warehouse stands to the west of it.

Large German bunker ('Alberta') in St. Julian

A little to the south of St. Julien is one of the smallest cemeteries in the Salient; Bridge House Cemetery. The name derives from that given to a nearby farmhouse. After the war, many cemeteries were being concentrated together to avoid too many small isolated cemeteries or burials on the land which was now returning to use. A figure of 50 was generally taken as the smallest number of graves in a cemetery which would not be concentrated. However, at Bridge House there are just 45 burials (five unknown), so this represents an unusual case. The cemetery is an original wartime one, made by the 59th Division at the end of September 1917. The majority of those buried here are from that Division, and had fallen towards the end of September, mainly in the Battle of Polygon Wood. The cemetery contains just three rows, one with just three graves. Interestingly, one man buried here (from the South Staffordshires) was at one time commemorated by a Memorial Cross which stood in Potijze Chateau Grounds Cemetery. (This information was provided by Terry Denham via the Great War Forum website.)

The tiny Bridge House Cemetery

The Monmouths memorial can be found in a small walled enclosure, a short distance along the road from Bridge House Cemetery. This commemorates Second Lieutenant Henry Anthony Birrell-Anthony and men of the 1/1 Monmouths. Birrell-Anthony was, before the War, an articled clerk with B. L. Reynolds of High Wycombe.

Memorial to Second Lieutenant Henry Birrell-Anthony and men of the 1st Monmouths

Sources & Acknowledgements

1901 Census

Will R. Bird: Thirteen Years After

Beatrix Brice: The Battle Book of Ypres

Great War Forum

Major & Mrs. Holt: Battlefield Guide to the Ypres Salient

Lt.-Col. Graham Hutchison: Pilgrimage

Library and Archives Canada website

J. E. Edmonds: Military Operations France & Belgium, 1915

Lost Generation 1418 discussion forum

Chris McCarthy: Passchendaele, the day by day Account

Paths of Glory website

The Times online archive